There are two things that you don’t want to do with any rechargeable battery on a routine basis:

- Overcharge it.

- Overdischarge it.

While the above are true for lead-acid batteries, they are particularly true of Lithium-Ion chemistries, but for different reasons.

With Lead-acid batteries:

- Lead-acid batteries – particularly the “flooded cell” types (e.g. those to which you can add water) can handle quite a bit of overcharging as long as the electrolyte level is maintained. “Sealed” batteries (e.g. AGM, or those that many mistakenly called “gel” cells) can handle some overcharging, but only to an extent before their pressure vents release accumulated gasses, reducing the amount of usable electrolyte, which is why they should never be “equalized”.

- Lead-acid batteries can also handle being run completely down – as long as you don’t keep them in that state for very long (a few days at most – as little time as possible) and don’t do it very often. In other words, if you run an otherwise healthy lead acid battery completely dead and immediately recharge it, little actual damage is likely to have been done other than taking a bit of life off it farther down the road. In cold-weather environments, while the degradation (primarily sulfation) is dramatically slowed, extremely deep discharge also reduces the specific gravity, raising the electrolyte’s freezing point, increasing the possibility of the battery being damaged/destroyed at very low temperatures if it does freeze.

With Lithium-ion batteries:

- If a battery is overcharged, it will start to chemically decompose. Gross overcharging – while tolerated at least briefly by lead-acid batteries – may result in a lithium-ion battery venting and/or exploding, possibly catching fire.

- If a battery is over-discharged it will chemically decompose, often with the contained lithium changing into a more volatile – and not useful – state. Severe over-discharging (e.g. below 2 volts per cell – this voltage varies depending on chemistry) can mean that the battery can never safely be charged again or, in some cases – if the voltage is only allowed to get down to this general area and not lower (again, the voltage varies according to chemistry) some special charging precautions are required (e.g. a specific, very low-rate trickle charging regimen) to “recover” this battery.

- There are also some specific temperature-related restrictions with lithium-type batteries regarding their use and charge/discharge and these are noted by their respective manufacturers.

Avoiding over-discharge:

The avoidance of overcharging is usually pretty easy: Just use the appropriate charging system – but over-discharge is a bit more difficult, particularly if the battery packs in question don’t have a “protection board” with them.

Lead acid batteries (almost) never come with any sort of over-discharge protection – one must usually rely on the ability of the device being powered (e.g. an inverter) to turn itself off at too-low a voltage and hope that the threshold is sensible for the longevity of a 12 volt battery system. For low-to-moderate loads (e.g. 1/10th “C” or so) a pretty safe “dead battery” voltage for a 12 volt lead-acid battery is around 11.7 volts – or somewhat higher for heavier loads. Again, after disconnect, it is not a good idea to keep it in a discharged state for any longer than possible.

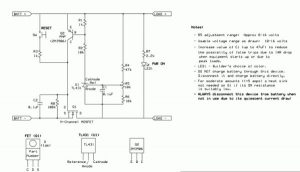

Read more: Disconnect circuit for 12 volt lead acid and lithium batteries