Computer chips, solar cells and other electronic devices have traditionally been based on silicon, the most famous of the semiconductors, that special class of materials whose unique electronic properties can be manipulated to turn electricity on and off the way faucets control the flow of water.

There are other semiconductors. Gallium arsenide is one such material and it has certain technical advantages over silicon – electrons race through its crystalline structure faster than they can move through silicon.

But silicon has a crushing commercial advantage. It is roughly a thousand times cheaper to make. As a result, gallium arsenide-based devices are only used in niche applications where their special capabilities justify their higher cost.

Cellphones, for instance, typically rely on speedy gallium arsenide chips to process the high-frequency radio signals that arrive faster than silicon can handle.

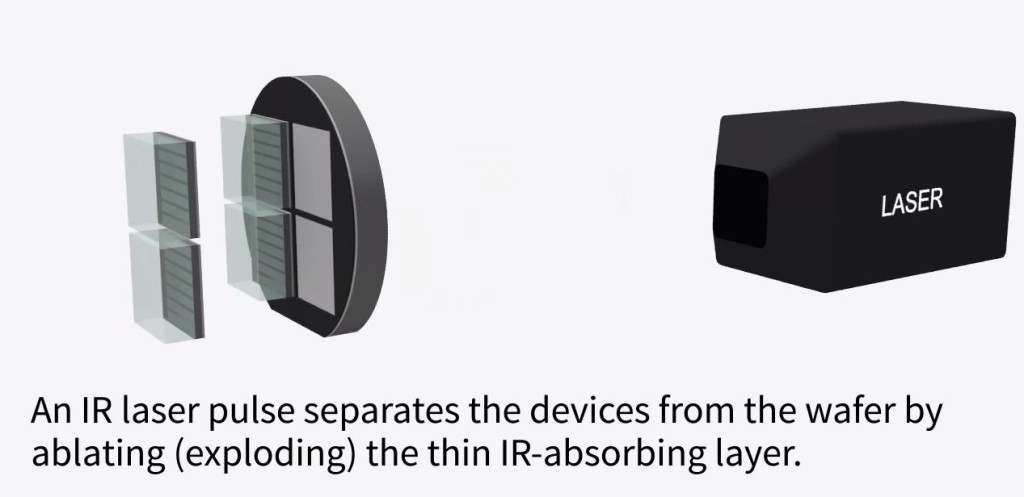

Now Stanford researchers have invented a manufacturing process that could dramatically reduce the cost of making gallium arsenide electronic devices and thus open up new uses for them, notably inside solar panels.

“Solar cells that use gallium arsenide hold the record when it comes to the efficiency at which they convert sunlight into electricity,” said Bruce Clemens, the professor of materials science and engineering who led this work.

But silicon-based solar is so much cheaper to make that gallium arsenide solar cells are relegated to exotic applications such as satellites. There, the main cost is launching the satellite into orbit, so gallium arsenide solar panels pay their freight by virtue of their greater photon-to-electricity conversion efficiency.

Clemens, who is the Walter B. Reinhold Professor in the School of Engineering, said the Stanford process could make gallium arsenide solar cells more practical on Earth.

Writing in the journal MRS Communications, Clemens and co-author Garrett Hayes, who recently earned his doctorate in materials science from Stanford, describe this new manufacturing process.

For more Detail : New process could make gallium arsenide cheaper for computer chips, solar cells